Do not pass Go. Do not collect 200 billion dollars.

After 4 years, hundreds of documents analyzed, interviews conducted, and courtroom hearings held, we have a verdict.

“Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly,” Judge Amit P. Mehta said in his ruling on August 5th.

Out of context, the decision feels like a conclusive end to Google. But there’s nuance and complexity that deserves attention before determining an appropriate punishment.

The DOJ needed to prove that:

- “General search services” is a market that can be monopolized.

- Exclusivity deals with 3rd parties to make Google the default search engine were anticompetitive.

- Being the default search engine was a major advantage due to the status-quo bias and choice architecture.

- The advantage in data and users from being the default search engine led to a distinct advantage in building a superior search engine.

- Google needs real consequences. Only removing the exclusivity deals doesn’t fix the decades of user data they leveraged to build a superior search engine.

The scope of this trial has been expansive. It encapsulates billions of dollars, multiple Fortune 50 companies, and a complicated economic ecosystem.

Judge Mehta’s 277-page opinion is comprehensive, logical, and transparent–even if it lacks remedies that will be proposed on Sept. 6th.

Let’s examine the skeleton of this trial, how Judge Metha came to his decision, and the behavioral economic principle–status quo bias–that serves as the foundation of the verdict.

Breaking Down the DOJ v. Google Antitrust Trial

Without getting philosophical in terms of whether monopolies are good or bad for a capitalist society, the goal of regulation at a government level is to protect consumers from limited options, unnatural price manipulation, poor product quality, and reduced innovation. Antitrust suits need a specific purpose.

In this case, Google was accused of violating the Sherman Antitrust Act which prohibits anticompetitive agreements.

Sidenote: For the purposes of this article, I am not going to address the ads side of this trial since it’s less relevant to Organic Search.

To argue that Google’s monopoly power in the general search service market and that their exclusivity deals were anti-competitive, the DOJ needed to establish that:

- “General search services” are a relevant product market and alternative sources for consumer searches, like specialized vertical providers (SVPs) and social media sites, are not adequate substitutes.

- Google’s exclusivity deals created a barrier to entry that prevented competitors from scaling and diminished the incentive to invest in innovation in general search.

Google’s Monopoly Power in the General Search Services Market

The DOJ argued that Google holds monopoly power in the general search services market through market share and natural barriers to entry for competitors.

Judge Metha was convinced that “general search services” are a relevant product market and only directly compete with other general search engines (like Bing and DuckDuckGO). Alternative sources for consumer searches, specialized vertical providers (like Amazon or Yelp) and social media platforms (like TikTok and Meta), are not adequate substitutes.

Here’s how Google stifles competition.

Direct and Indirect Barriers to Entry for the General Search Services Market

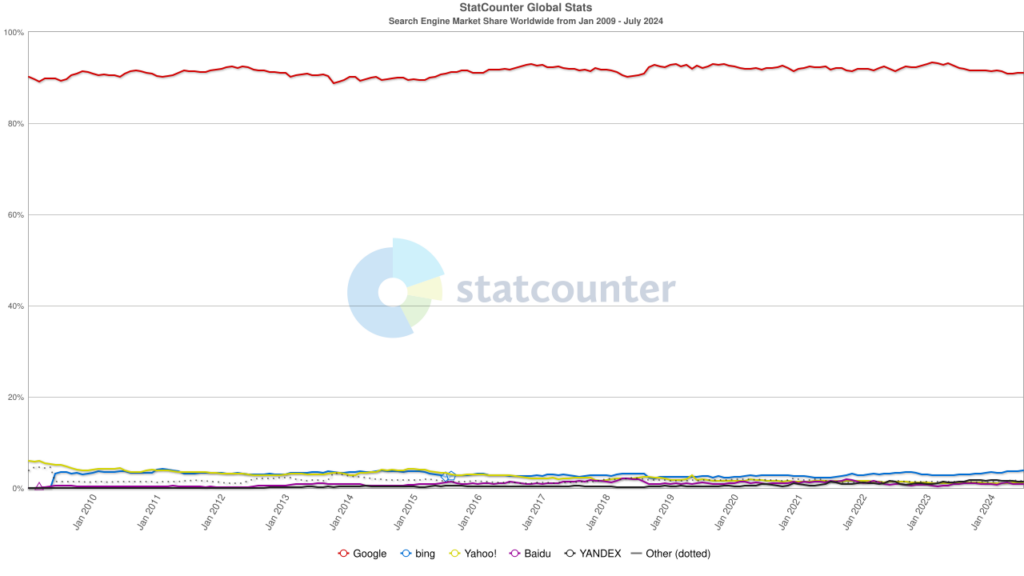

Google dominates with an 89.2% share of general search services by query volume, which increases to 94.9% on mobile devices.

Several barriers to entry protect Google’s market dominance:

- High Capital Costs: Building and maintaining a competitive search engine requires billions of dollars, including the development of ad tech for monetization. It would cost Apple, at least $20 billion to launch a competitive search engine, more to maintain and monetize it.

- Control of Key Distribution Channels: Google’s contracts and ownership of key platforms like Chrome make it financially unfeasible for competitors to secure similar deals.

- Brand Dominance: “Google” is so ingrained in popular culture that it’s used as a verb, driving even Bing users to search for “google.com.” This brand power incentivizes partners to keep Google as the default search engine.

- Scale: Data at scale significantly improves search result quality. Google to improve its product with more user behavior and query-type insights. Google exploits those scale advantages by leveraging user behavior data (via Chrome) and insights from an expansive query universe.

Judge Mehta agreed with the merits of the argument and dismissed Google’s counterarguments which consisted of:

Counterargument 1:

- Google: DuckDuckGo and Neeva created competing products refuting the barrier to entry.

- Judge Mehta: New entrants did not take significant market share from Google. Thus, it doesn’t preclude the barrier to entry.

Counterargument 2:

- Google: The existence of AI removes barriers to entry for new entrants.

- Judge Mehta: Maybe eventually, but not yet.

Counterargument 3:

- Google: Google dethroned Yahoo. So it can be done.

- Judge Mehta: The market factors are different. It’s not the same environment.

Counterargument 4:

- Google: Search output has grown.

- Judge Mehta: The argument of market growth doesn’t apply to search since it doesn’t result in excessive costs.

Judge Mehta’s verdict established that Google was a monopoly for general search services.

Exclusivity Deals and Their Anti-Competitive Impact

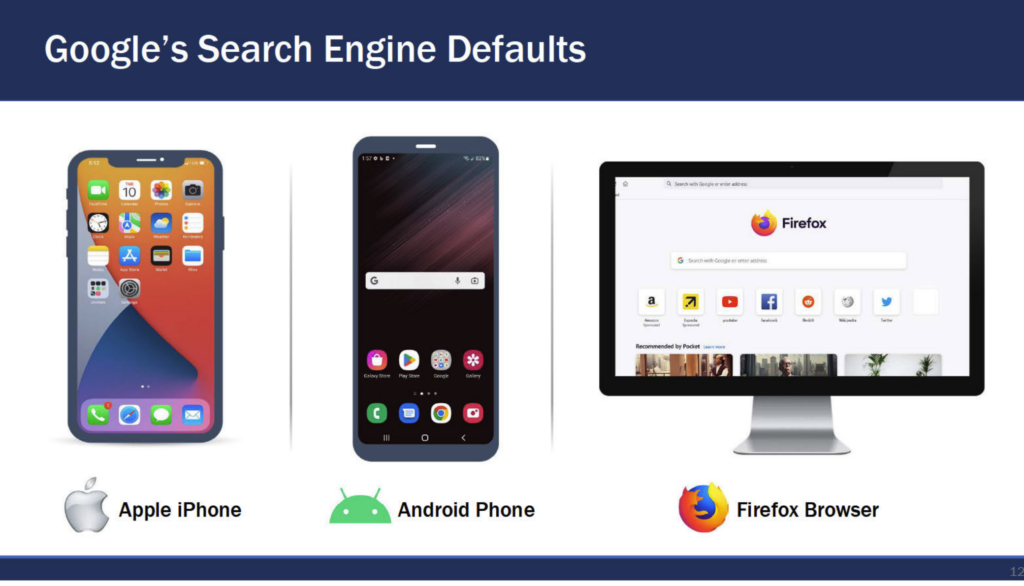

Central to the trial is the role of Google’s exclusivity deals with major partners, including browser developers (Apple, Mozilla), Android device manufacturers (Samsung, Motorola, Sony), and wireless carriers (AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile). These deals establish Google as the default search engine, creating significant barriers for competitors.

- Exclusionary Conduct: The court found that Google’s exclusivity agreements effectively shut out competition. Partners often concluded that it was financially infeasible to switch default search engines or seek more flexibility due to the massive revenue share payments they receive from Google.

- Browser Agreements: Google is the default search engine out-of-the-box on major browsers like Safari and Firefox.

- Android Agreements: Google’s agreements with Android manufacturers require that the Google Search Widget be featured prominently on home screens, with Chrome pre-installed as the default browser.

- Market Foreclosure: These agreements prevent competitors from scaling by denying them access to the user queries necessary for improving and sustaining a search engine. Google’s dominance in these default positions gives it additional search volume, further entrenching its market power.

Effects on Innovation and Competition

The DOJ contends that Google’s monopoly power and exclusivity deals have not only foreclosed the market to competitors but also diminished the incentive to innovate.

- Scale Advantage: Google’s massive user base allows it to continuously improve its search quality by collecting more user data. This data is used to enhance search algorithms, expand the web index, and refine search results. The cycle of more users leading to better search quality, which attracts even more users, reinforces Google’s market position.

- Innovation Incentive: The lack of genuine competition has arguably reduced Google’s incentive to innovate. While Google has a history of innovation, the DOJ points out that Google spends seven times more on securing default positions than on research and development.

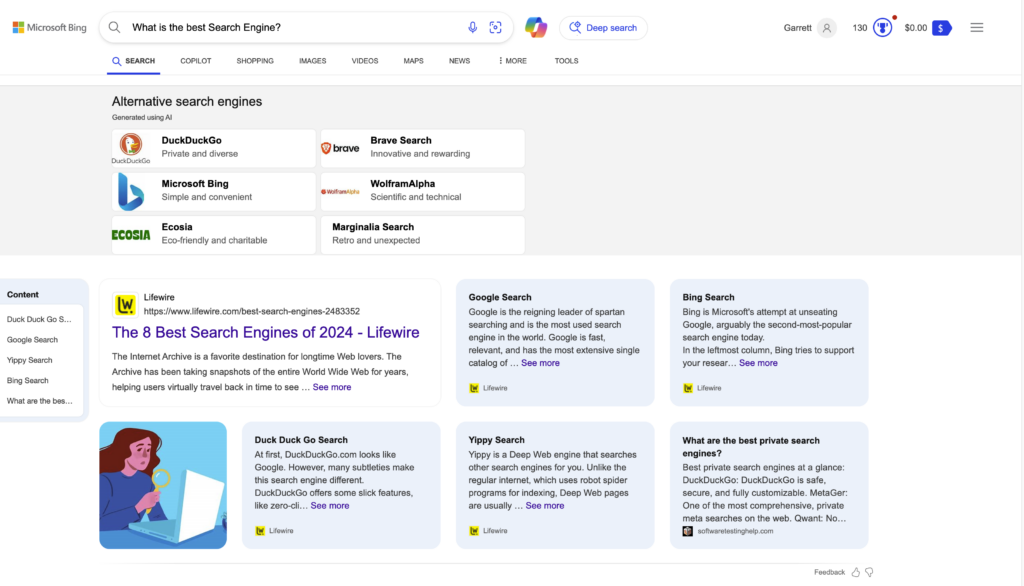

- Response to Competition: One notable exception is Google’s launch of its AI chatbot, Bard (now Gemini), which was a direct response to Microsoft’s integration of AI with Bing (BingChat, now Copilot). This suggests that Google does innovate when faced with serious competition, but the general lack of competition has limited such incentives.

The trial underscores the argument that Google’s dominance is not just a product of its superior search engine, but also of strategic exclusivity deals that have stifled competition and innovation. The DOJ’s case emphasizes the need for a competitive market where multiple players can innovate and provide diverse search experiences, ultimately benefiting consumers.

For additional great breakdowns of the decision from a legal and SEO angle, read these X threads by Jason Kint and Marie Haynes.

Sorry, my "bam!" was cryptic.

— Jason Kint (@jason_kint) August 5, 2024

Google has violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act by maintaining its monopoly in two product markets in the U.S....

It's 286 pages - be back with a thread shortly along with implications for the adtech antitrust trial starting in five weeks. /1 pic.twitter.com/3xAVLuiKH1

👀

— Marie Haynes (@Marie_Haynes) August 5, 2024

The judge in the DOJ vs. Google trial has ruled the Google violated antitrust laws.

I'm no lawyer, but I'm super interested in this case. I thought my day was done, but instead, let's dig in and see what's interesting in this 286 page document.

(David has brought me… pic.twitter.com/9BzLRUUPRg

Understanding Status-Quo Bias and Choice Architecture

Why were the exclusivity agreements such an important part of the argument? That’s where behavioral economics and a subtle, but impactful cognitive bias came into play.

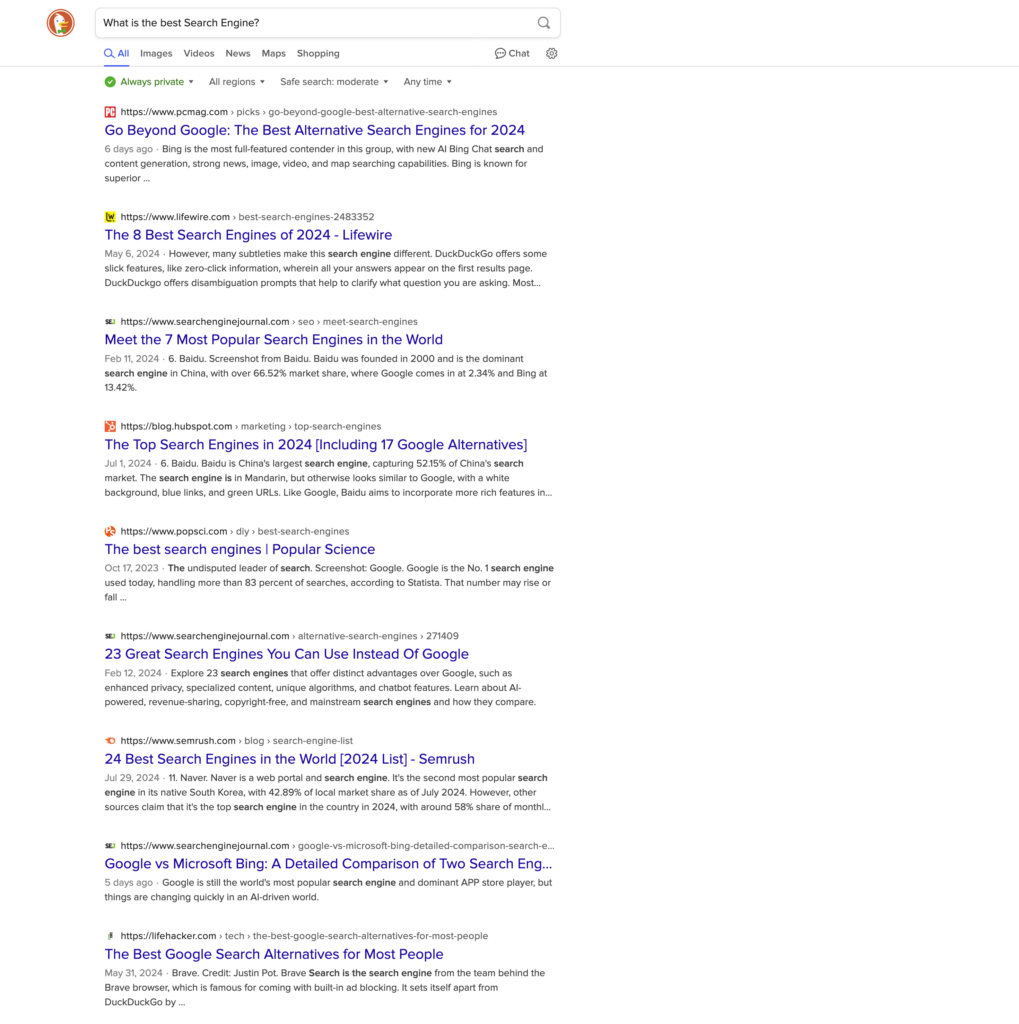

Have you ever considered making Bing your default search engine? No, nobody has. But what about DuckDuckGo?

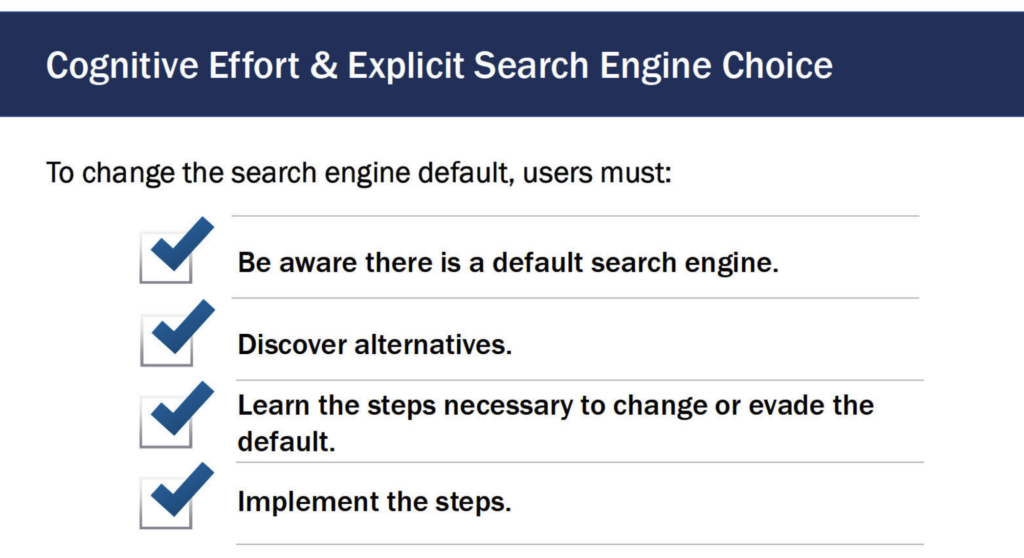

If you have, you’ll realize that while it’s not particularly difficult, it’s annoying. Now consider that any device that you use, your phone, laptop, or tablet comes with a default search engine.

Every time you click a link in an email. Whenever you pose a question to a voice assistant. When you fire up your web browser. A preinstalled default search engine sits on the homepage or provides the default results.

Professor Antonio Rangel, a renowned expert in behavioral economics, provided critical testimony for the DOJ.

His responsibilities as an expert witness were to:

- Evaluate the impact of Google’s search defaults.

- Compare the impact of search defaults on mobile devices versus personal computers.

- Evaluate the impact of defaults on consumers’ decisions regarding privacy in search.

Rangel explained how psychological factors like status quo bias and choice architecture shape user behavior and how that might have helped Google achieve an advantage in users, scale, and maintaining its monopoly.

Status quo bias (or default bias) is the tendency for people to stick with pre-set options simply because it’s easier than making a change.

Rangel highlighted that even when users are aware they can switch to a different search engine, the cognitive effort required to do so often stops them from making a change. This friction—the small but significant obstacles involved in switching—keeps users with Google and solidifies its dominance.

Rangel’s testimony also evaluated the extensive network of partnerships that Google has established to maintain its position as the default search engine. These partnerships include deals with major players like:

- Apple: Google pays billions of dollars annually to be the default search engine on Safari, the web browser for iPhones, iPads, and Macs.

- Firefox: Google pays to be the default search engine on the Firefox browser.

- Android OEMs: Google has agreements with Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) like Samsung and others, ensuring Google’s search engine is the default on Android devices.

- Carriers: Google also partners with mobile carriers to keep its search engine as the default on the phones they sell.

These payments aren’t small change; in some cases, they amount to billions of dollars annually. These deals effectively lock in Google’s position as the default search engine across a wide range of devices and platforms, further entrenching its dominance.

Choice architecture refers to how these options are presented to users, guiding them toward a particular choice. Google has mastered this by ensuring it is the default search engine on the vast majority of devices and browsers.

This isn’t just a matter of convenience—it’s a deeply rooted behavior that influences choices in many areas of life. For instance, Dr. Rangel shared real-life examples in his testimony:

- When organ donation is the default option participation rates are 99% (in Austria) as opposed to 12% (Germany) when participation requires potential donors to opt-in.

- In a 401(k) plan study, an opt-in default increased participation from 37% to 86%.

- For end-of-life care, 77% of patients chose comfort-oriented directives when default, versus 43% when life extension was the default.

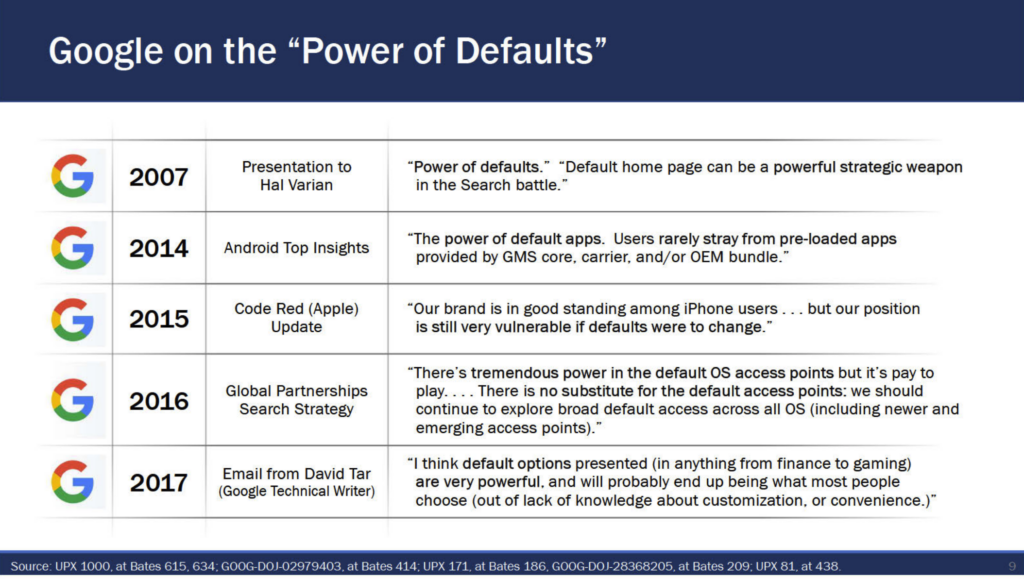

Using Google’s own research and communications, Dr. Rangel found several examples that revealed Google’s intentional strategy of using status-quo bias as a psychological advantage.

Ensuring that Google Search was the default was critical to the competitive advantage.

This friction is particularly strong on mobile devices, where changing the default search engine is significantly more difficult than on a desktop. On desktops, switching search engines might involve a few clicks, but on mobile devices, it often requires navigating through multiple menus, making it more cumbersome and less likely that users will make the effort.

As a result, most users stick with Google, especially on mobile, where the process of changing the default is intentionally more challenging.

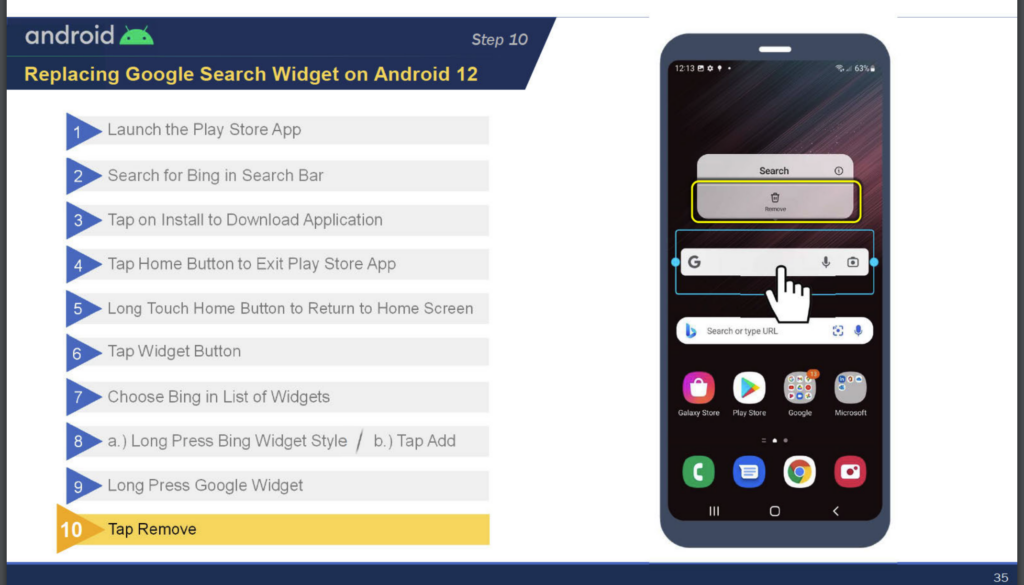

Take this 12-step example to change the Google Search widget on Android phones that Dr. Rangel demonstrated:

Google isn’t the only tech giant that builds massive walled gardens.

- Apple employs a closed ecosystem approach, where access to its devices is tightly controlled through the App Store. Developers must pay or meet stringent criteria to offer their apps, creating a walled garden that keeps users within Apple’s ecosystem.

- Amazon uses default settings and algorithms to influence user behavior. They promote their own brands or preferred sellers by default, guiding users towards specific products.

- Social media platforms curate content through algorithms designed to maximize engagement, subtly steering users toward certain types of interactions and keeping them within the platform’s ecosystem.

But are these practices on their own platforms illegal? Not necessarily and not litigated…yet.

These practices aren’t even new. The Microsoft antitrust trial in the 2000s dealt with similar issues, where Microsoft’s dominance as the default web browser on most PCs led to accusations of anti-competitive behavior. Like Google today, Microsoft was accused of using its default status to stifle competition.

The Counterargument: Should Google Be Punished for Product Superiority?

While the Google antitrust trial focuses heavily on status quo bias and choice architecture, it’s important to recognize that Google’s dominance isn’t solely due to these factors.

Most users stick with Google because it’s a superior product. Google has invested heavily in its search engine, making it fast, accurate, and highly relevant to users’ needs. Competitors have struggled to match its level of quality.

Bing and DuckDuckGo, Google’s most notable competitors, can’t capture significant market share.

Bing offers a relatively strong alternative, particularly with its integration into Microsoft products. Aside from Google and Apple, it’s the only other internet index. But it still lags behind Google in terms of search accuracy, speed, and relevance.

DuckDuckGo appeals to users concerned with privacy, offering a search engine that doesn’t track user data. However, its focus on privacy often comes at the expense of the comprehensive and tailored search results that Google provides.

Neeva, a subscription-based search engine, entered the market with the promise of a privacy-focused, ad-free experience. Despite its noble intentions, Neeva ultimately couldn’t survive in a market dominated by Google, highlighting just how difficult it is for new entrants to compete, even when they offer distinct value propositions.

Watch the episode: iPullRank founder, Mike King interviewed Neeva founder Sridhar Ramaswamy on the Rankable Podcast last year.

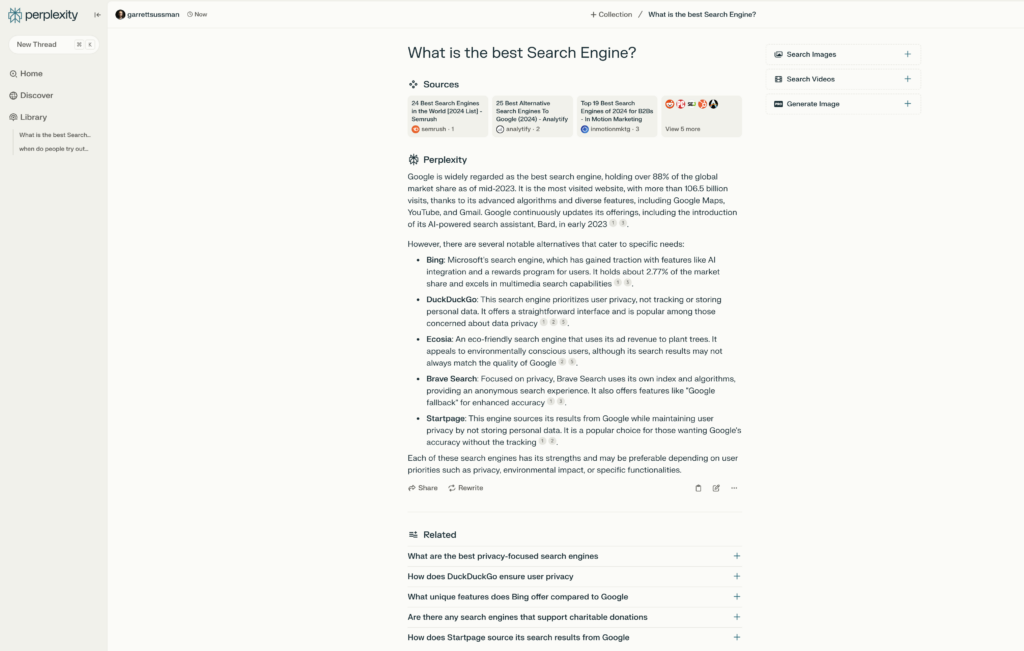

Looking ahead, Perplexity is an emerging competitor that is trying to carve out a niche in the search engine market. Perplexity is designed to combine AI-driven search with a focus on providing direct answers, similar to how a virtual assistant might respond. While promising, it remains to be seen whether Perplexity can overcome the challenges that have faced other competitors and gain a foothold in a market where Google sets the standard.

For most of us, Google isn’t just the default—it’s the preferred choice. This preference is based on performance. Google’s search engine delivers results that are often more comprehensive and tailored to what users are looking for. The speed and efficiency of Google’s search algorithms set a high standard that other search engines have yet to meet consistently.

Google argued that younger people actually prefer TikTok with 62% using it as their search engine. There was also the narrative last year that billions of people were appending Reddit to their searches (Reddit didn’t replace Google in this instance).

Google used Apple Maps as another example, and for me it hits close to home. Despite Apple Maps being the default tool on CarPlay, I always choose to use Google Maps for driving directions. It’s not driven by status quo bias, Google Maps offers a better user experience—more accurate directions, better traffic data, and a more intuitive interface. Even though it requires effort to make the switch, the superior quality of Google Maps makes that effort worthwhile.

Rangel’s testimony even acknowledged that the effectiveness of status quo bias can be tied to the quality of the product. When the default product is superior, the bias is stronger because users have less incentive to switch. When the default option is inferior, users are more likely to go through the friction to find something better.

But the criticism of Google’s declining quality hasn’t impacted market share. At some point, it may. At that time, you’d be able to make a stronger argument that the status quo bias isn’t as critical to the competitive advantage.

Google’s success is as much about delivering a superior product as it is about leveraging default settings. Penalizing Google simply for being the top performer could set a dangerous precedent where companies are punished for excelling in their fields.

In my opinion, that argument lacks teeth when you realize that Google’s search engine became a better product in large part due to the scale of user data.

The Broader Impact of the Status Quo Bias on SEO

The Google antitrust trial isn’t just a legal battle—it has significant implications for SEO and marketing strategies. At the heart of this case are status-quo biases and choice architecture, concepts rooted in behavioral economics, which heavily influence how users search and how marketers need to approach their SEO strategies.

More SEOs need to consider cognitive biases across their SEO strategy.

Most searches today are driven by what Daniel Kahneman describes as System 1 thinking—the type of thinking that is fast, automatic, and instinctive. When users perform a search, they’re often not engaging in deep, deliberate thought. Instead, they’re relying on habits formed over years of using Google. This means that when they search, they’re not thinking, “Should I use Google, Bing, or DuckDuckGo?” They simply open Google and start typing.

Status quo biases reinforce this behavior.

Because Google is the default search engine for most users, they rarely think about switching to another option. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle: users instinctively go to Google because it’s what they’re used to, and Google remains dominant because users continue to reinforce its position through their habitual use.

For SEO professionals, this ingrained behavior has crucial implications. SEO strategies must recognize that most users are deeply rooted in their Google-centric habits. This means that optimizing for Google is not just a best practice—it’s a necessity. Even as the antitrust trial unfolds and potential remedies are discussed, Google is likely to remain the dominant search engine for the foreseeable future.

This isn’t to say that SEOs should ignore other search engines, but rather that they should prioritize Google while keeping an eye on emerging trends. Any significant shift in market dynamics, whether through legal outcomes or technological advancements, will take time to materialize. Meanwhile, Google will continue to be the primary platform through which users access the web.

As marketers and SEOs plan for the future, it’s essential to stay informed about developments in the Google antitrust case and consider how changes might eventually impact search behavior. However, given the strong influence of default biases and the fact that most searches are conducted through System 1 thinking, it’s reasonable to expect that Google’s dominance will persist, at least in the short to medium term.

Will New AI Search Interfaces Circumvent Google's Status Quo Bias Advantage?

While the rise of AI-driven search engines poses new challenges to Google’s dominance, it’s important to recognize that Google itself is heavily invested in AI.

Google’s AI tools, including its integration of AI into traditional organic search and the development of Gemini, are part of its strategy to stay ahead in the rapidly evolving search landscape. Gemini, Google’s next-generation AI model, aims to enhance search by providing more intuitive, context-aware results that integrate seamlessly with users’ search habits. By incorporating AI directly into its existing infrastructure, Google is working to ensure that it remains the go-to search engine, even as new technologies emerge.

Apple Intelligence is another player to watch, though it’s important to note that Siri, Apple’s AI-powered assistant, is more than just a search engine. While search is a component of Siri’s capabilities, Apple Intelligence is designed to provide a broader range of functions, from answering questions to controlling smart home devices. However, as Apple integrates OpenAI’s technology into Siri, we can expect it to become a more powerful tool for retrieving information, potentially offering a seamless, AI-driven search experience that could challenge Google’s dominance, particularly among users already embedded in Apple’s ecosystem.

Beyond Google and Apple, other AI-driven tools like SearchGPT recently emerged as potential competitors. SearchGPT leverages large language models to deliver personalized, conversational search results, moving away from the traditional model of presenting a list of links. This could fundamentally change how users interact with search engines, especially for queries that require nuanced, context-specific answers.

Perplexity (mentioned previously) blends AI with traditional search engine features, aiming to offer a more interactive and responsive search experience. By assisting users in refining their queries and delivering precise answers, Perplexity could cater to users who prefer more detailed, conversational interactions with their search engine.

Facebook’s LLaMA (Large Language Model Meta AI) represents another potential disruptor in the search space. As an open-source model, LLaMA could enable the development of new, AI-powered search engines, fostering innovation and competition in a market currently dominated by a few key players.

These developments point to a future where longer-tail queries and natural language searches become more prevalent.

As we grow accustomed to interacting with AI tools that understand and respond to more complex, conversational prompts, the way people search is likely to evolve. This shift in behavior means that brands need to adapt their content strategy.

Creating more specific, personalized content that caters to these longer-tail queries could become increasingly important, as search engines—AI-powered or not—focus on delivering results that match the nuances of users’ inquiries.

While AI-driven tools are still in their early stages, their potential to disrupt the search market is significant. As these technologies continue to develop, we may see new competitors emerge that challenge the status quo, providing alternatives to Google’s current dominance.

The Need for More Competition in the Search Engine Market

Google deserves to be the market leader. It’s not hyperbole to call Google Search the most important society-changing product in the last 30 years.

More competition in the search engine market would benefit everyone—people, businesses, and the broader Internet ecosystem.

Today, only a few companies have the resources to index the entire internet. In practice, this means that only Google and Bing operate full-scale indices that power search engines.

Apple also maintains a significant internet index, although it primarily uses this data to power its services. The scarcity of companies capable of indexing the web means that a few players control how most people access information online.

The critical issue with this concentration of power: editorial bias.

Every search engine, whether AI-powered or traditional, operates based on algorithms that determine what content gets surfaced and how it is ranked. These algorithms are designed by corporations that decide what is considered the most relevant and highest-quality content.

While these systems aim to deliver the best results, they are inevitably influenced by the parameters set by their engineers. Search engines (and indices) are not neutral; they shape the results we see.

Given the vast amount of content on the internet, much of which is low-quality or irrelevant, search engines play a crucial role in filtering out the noise and presenting people with the most useful information (in theory).

However, when only a few companies control this process, it raises concerns about the diversity of perspectives and the kinds of content that are elevated or suppressed.

- Greater diversity in search would lead to a broader range of perspectives. Exposure to different ways of looking at the world would benefit society.

- More competition in the search engine market would result in different algorithms that prioritize different types of content. True hidden gems and expert information could be surfaced.

- This diversity would benefit users by providing multiple ways to discover and evaluate content, reducing the risk of any one company dominating the flow of information.

Increased competition could spur innovation in personalized search. That’s my own hope for a future version of Apple Intelligence.

Imagine a search engine that goes beyond traditional web searches and integrates seamlessly with all aspects of your digital life—your social media, your personal data on your phone, your photos, and more. Such a search engine could offer highly personalized results that take into account your specific context, like where you are, what you do, your history, and your preferences. I covered why that’s important in my MozCon presentation on cognitive bias and SEO.

This kind of deep personalization could make search engines far more effective at delivering exactly what you need, tailored to your unique circumstances.

While these innovations would require people to be comfortable sharing more personal data, the potential benefits in terms of relevance and efficiency could be significant. A truly personalized search engine could transform how we access information, making it more aligned with our individual needs and circumstances.

What’s Next for Google? Striking a Balance

The antitrust trial is over.

Google’s dominance in the search engine market is the result of a complex mix of factors: a powerful blend of status-quo bias that keeps users within its ecosystem, the undeniable superiority of its product that outperforms its competitors, and a notable lack of competition that limits alternatives.

But what does this mean for the future of search and for those in the SEO industry?

First and foremost, it’s crucial to recognize that Google’s position isn’t likely to be dethroned overnight. Even with the inevitable remedies of the antitrust trial and the emergence of AI-driven competitors, the strength of Google’s brand, its extensive partnerships, and its integration of cutting-edge AI tools mean that it will likely remain the dominant search engine for the foreseeable future.

However, things are changing.

AI-powered search engines like SearchGPT and Perplexity could carve out new niches and search audiences. Apple Intelligence could have an outsized impact when released. And we can’t ignore Google’s integration of AI Overviews more comprehensively over time.

These products promise to shift the focus of search from traditional methods to more conversational, personalized experiences. As these technologies evolve, they could gradually alter user behavior, making the search ecosystem more diverse and competitive.

For SEOs, this means adapting to a world where Google remains central, but where it’s also essential to stay ahead of emerging trends. Longer-tail queries and more natural language searches are becoming increasingly important, especially as AI-driven tools gain traction. SEOs should focus on creating content that is specific, relevant, and personalized to cater to these evolving search habits.

SEOs should keep an eye on developments beyond Google. As new search options enter the market, there may be opportunities to optimize for different platforms and to experiment with content strategies that resonate across various search engines, LLMs, and SVPs.

In the end, striking a balance will be key. While Google will remain a cornerstone of any SEO strategy, the smart play is to prepare for a more dynamic, multi-platform future. Stay adaptable, informed, and ready to innovate. Organic Search is evolving as the search preferences of your audiences shift around you, independent of the remedies of this monopoly.

Interested in putting together an SEO strategy that supports your other marketing channels and future-proofs your brand? iPullRank has a few spots for new clients.

Contact us to set up a discovery call and discuss your needs.