A common complaint about Google Search Console (GSC) is that the data is “inaccurate” when compared to Google Analytics results.

You know the situation.

We’ve all done it.

You try to line up traffic to landing pages from analytics with clicks from Google Search Console and the numbers are nowhere near close!

Then you mumble something about “not provided” and send an instant message to a friend about the good old days when you could see keywords in your analytics.

While it is a question of precision, it’s not a question of accuracy per se.

That data disparity is actually by design.

Let’s dig into the details and figure out why that is.

Google Search Console & Google Analytics Don’t Measure the Same Things

The short explanation is that the two data sources have different measurement methodologies.

GSC is built from query and click, or selection, logs, so the data will be somewhat similar to what you might expect from your own access log files (you know, the files you plead with DevOps to get access to for log file analysis).

Conversely, your analytics package collects data from the clickstream via JavaScript. That inherently introduces a lot of variables for how things can be measured as well as what those things are.

In order to better understand what causes the differences in data between GSC and analytics, you first need to understand how each tool collects and understands user behavior data.

The Anatomy of Query & Selection (Click) Logs

Google’s relentless quest for search quality naturally leads them to track a wealth of data points for every search, and every searcher, in hopes of gaining a complete understanding of what’s happening in the SERPs.

While they have indicated many times that they don’t allow clicks and click-through rates to influence rankings, despite evidence to the contrary, they have also said that they use click data for evaluation of performance.

This has been one of the ongoing arguments between public-facing Googlers and SEOs.

Personally, I believe Google’s side of it to be a semantic argument.

There are several evaluation measures that are standard to information retrieval such as:

- Clicks.

- SERP abandonment.

- Session success rate.

- Etc.

As you might imagine, Google has its own flavor of this called the Clicks, Attention and Satisfaction model (read Bill Slawski’s explanation if you need a translation).

It being discussed in a paper called “Incorporating Clicks, Attention and Satisfaction into a Search Engine Result Page Evaluation Model” combined with the click-based methodology highlighted in the Time-based Ranking patent suggests that someone at least took the time to think about how clicks might impact rankings.

According to Eric Schmidt’s testimony in 2011, Google did “13,111 precision evaluations.” That would be an average of ~35 per day.

So, it’s logical to assume that, if you’re always evaluating in a production environment, as the Search team is, then there is always potential for user clicks to impact rankings.

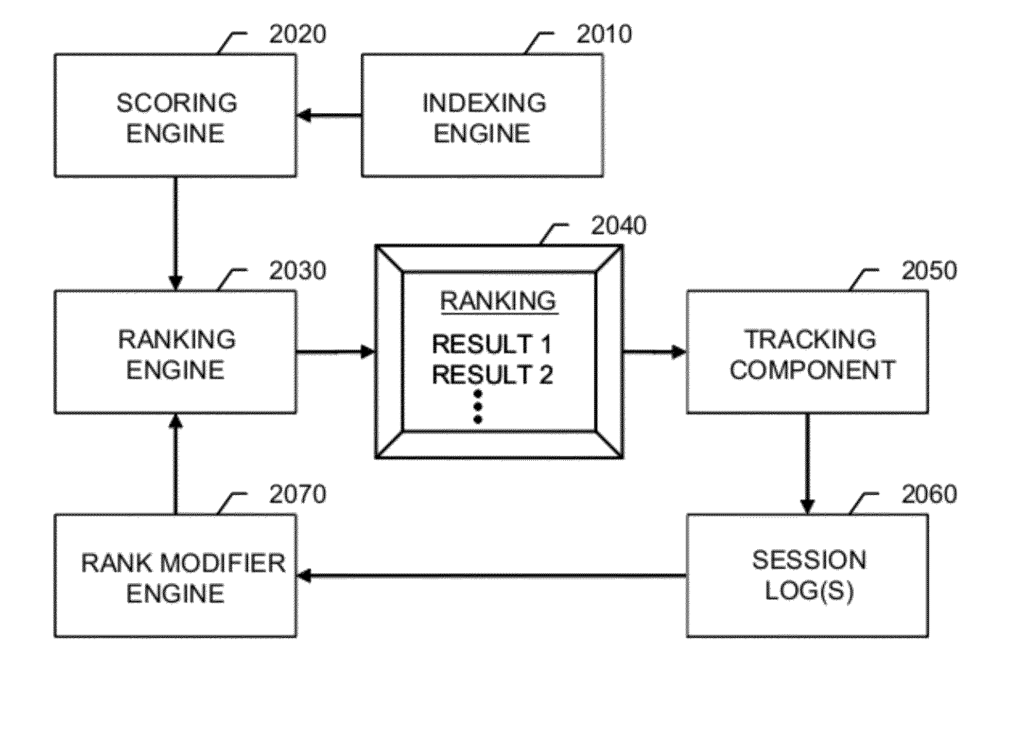

And then there’s this section from the Modifying search result ranking based on corpus search statistics patent that talks about search logs and how they might inform rankings in the future:

“The information stored in the session log(s) 2060 or in search logs can be used by the rank modifier engine 2070 in generating the one or more signals to the ranking engine 2030. In general, a wide range of information can be collected and used to modify or tune the signal from the user to make the signal, and the future search results provided, a better fit for the user’s needs. Thus, user selections of one or more corpora for issuing searches and user interactions with the search results presented to the users of the information retrieval system can be used to improve future rankings.”

What’s most interesting, however, is the concept that these logs feature a lot of noise in addition to their more valuable signals.

That suggests that taking the clicks completely at face value would be a mistake.

What type of noise are we talking about?

Well, for example, how many impressions are represented by ranking tools?

How many times do you hit enter on autosuggest and then realize that it triggers a search for “fan” instead of “fantastic 4?”

Or, what about when you’re scrolling on mobile and accidentally fat finger the wrong result?

These are all examples of how the data Google collects could feature a hefty amount of inaccuracies and they need to account for them.

Thanks for allowing me that aside.

OK, So What’s in the Log Files?

If the, now-defunct, Google Search Appliance documentation is any indication (which it may not be), query and click logs are simply text files that record data about users and their interactions with the SERP.

The documentation discusses search logs, which may or may not be the same as query and click logs as they are referred to in Google’s patents.

Despite being a simplified version of the system, it gives us some idea of what is tracked – features of the user, their query, and features of what they click on.

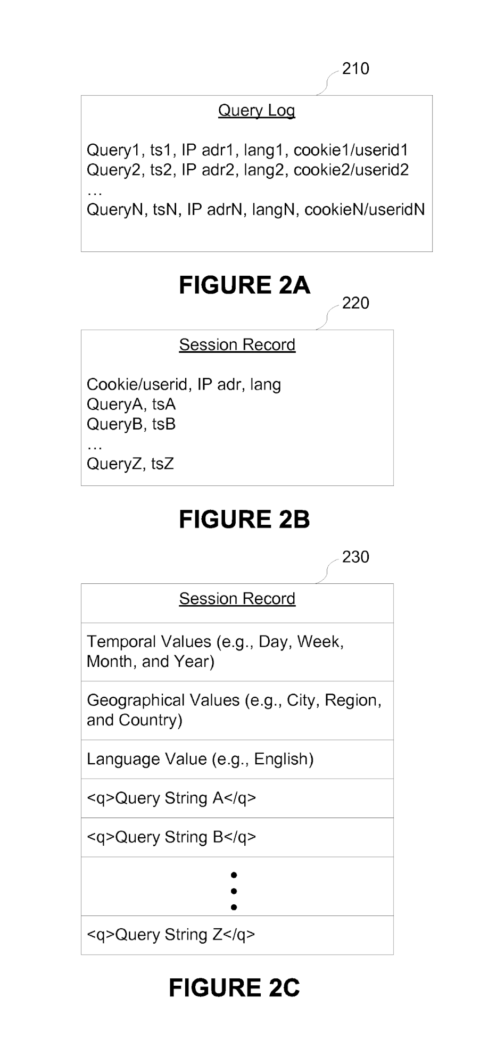

Digging deeper, in Google’s Systems and methods for generating statistics from search engine query logs patent, they talk a bit more about how a system that could power a tool such as Google Trends might operate.

For this discussion, I’m assuming that the underlying dataset is similar to, if not the same as, what powers Google Search Console and the Google Ads Keyword Planner.

They talk about the query logs as follows:

“A web search engine may receive millions of queries per day from users around the world. For each query, the search engine generates a query record in its query log. The query record may include one or more query terms, a timestamp indicating when the query is received by the search engine, an IP address identifying a unique device (e.g., a PC or a cell phone) from which the query terms are submitted, and an identifier associated with a user who submits the query terms (e.g., a user identifier in a web browser cookie).”

In other words, the search engine query logs are a bit more robust version of the GSA search logs.

The authors further explain in a bit more detail later in the patent with a discussion of how cookies, devices, user language, and location are tracked as well.

They also provide the following figure to give a visual representation of the data collected in the query log:

Giving more color to the system, the patent discusses this concept of a session record, which is a mechanism to determine if a given user has performed the same or similar searches within the given timespan.

This is especially important when it comes to measurement and reporting of impressions and/or search volume:

“A query session record includes queries closely spaced in time and/or queries that are related to the same user interest. In some embodiments, the query session extraction process is based on heuristics. For example, consecutive queries belong to the same session if they share some query terms or if they are submitted within a predefined time period (e.g., ten minutes) even though there is no common query term among them.”

The heuristics referenced in the above are perhaps the core of why Search Console and your analytics package will never match up.

Essentially, what the author is saying is that Google makes a decision in its query logging to determine if searches in your session are unique enough to be recorded as distinct.

Therefore, what you may believe to be two distinct visits to your site because they came from two different searches that landed on two different landing pages could potentially be considered one search and thereby one impression depending on how it is logged in Google’s query logs.

Click logs, on the other hand, feature more information on the behavior of the user once they have been presented with a series of results.

The Modifying search result ranking based on corpus search statistics patent reveals what can be stored in this dataset (emphasis mine):

“The recorded information, including result selection information, can be stored in session log(s) 2060. In some implementations, search data and result selection information are stored in search logs. In some implementations, the recorded information includes log entries that indicate, for each user selection, the query (Q), the document (D), the time (T) between two successive selections of search results, the language (L) employed by the user, and the country (C) where the user is likely located (e.g., based on the server used to access the IR system). In some implementations, other information is also recorded regarding user interactions with a presented ranking, including negative information, such as the fact that a document result was presented to a user, but was not clicked, position(s) of click(s) in the user interface, IR scores of clicked results, IR scores of all results shown before the clicked result, the titles and snippets shown to the user before the clicked result, the user’s cookie, cookie age, IP (Internet Protocol) address, user agent of the browser, etc. Still further information can be recorded, such as the search results returned for a query, where the search results are content items categorized into one or more corpora. In some implementations, similar information (e.g., IR scores, position, etc.) is recorded for an entire session, or multiple sessions of a user. In some implementations, the recording of similar information is not associated with user sessions. In some implementations, such information is recorded for every click that occurs both before and after a current click.”

While Google Search Console only surfaces a fraction of this information, it’s pretty clear how the Search Analytics tool is effectively a limited user interface built on top of this dataset.

What’s interesting here is the mention of activities that may happen across a SERP.

This is an indication that not only is every click tracked, but the features behind what generated the position of a result in a SERP.

What Determines a Click?

The public-facing documentation of Google Search Appliance does not indicate what is considered a click or an impression.

For instance, if I search for a keyword and click a result, hit back, and click the same result again, is Google considering that two distinct clicks or one?

The Systems & Methods for Generating Statistics from Search Engine Query Logs patent, however, gives some insight into the answer to that question.

The first thing to know is that they often sample the data. This makes a lot of sense in the Google Trends environment.

However, the author does note that there are use cases where they may not sample the data.

“To get reliable statistical information from the query log 108, it is not always necessary to survey all the query records (also herein called log records or transaction records) in the query log. As long as the statistical information is derived from a sufficient number of samples in the query log, the information is as reliable as information derived from all the log records. Moreover, it takes less time and computer resources to survey a sub- sampled query log. Therefore, a query log sampling process 110 can be employed to sub- sample the query log 108 and produce a sub-sampled query log 112. For example, the sub- sampled query log 112 may contain ten percent or twenty percent of the log records in the original query log 108. Note that the sampling process is optional. In some embodiments, the entire query log 108 is used to generate statistical information.“

Google also appears to deeply consider that two queries similar queries can represent one search.

This line of thinking is a core component that yields a difference in measurement between tools.

As Google has more recently moved to give the singular and plural versions of keywords the same search volume, much to the chagrin of the search community, it’s valuable to see an internal perspective on the matter.

I have presented their discussion from the patent in its entirety below (emphasis mine):

“For example, the user may first submit a query “French restaurant, Palo Alto, CA”, looking for information about French restaurants in Palo Alto, California. Subsequently, the same user may submit a new query “Italian restaurant, Palo Alto, CA”, looking for information about Italian restaurants in Palo Alto, California. These two queries are logically related since they both concern a search for restaurants in Palo Alto, California. This relationship may be demonstrated by the fact that the two queries are submitted closely in time or the two queries share some query terms (e.g., “restaurant” and “Palo Alto”).”

“[0035] In some embodiments, these related queries are grouped together into a query session to characterize a user’s search activities more accurately. A query session is comprised of a one or more queries from a single user, including either all queries submitted over a short period of time (e.g., ten minutes), or a sequence of queries having overlapping or shared query terms that may extend over a somewhat longer period of time (e.g., queries submitted by a single user over a period of up to two hours). Queries that concerning different topics or interests are assigned to different sessions, unless the queries are submitted in very close succession and are not otherwise assigned to a session that includes other similar queries. The same user looking for Palo Alto restaurants may submit a query “iPod Video” later for information about the new product made by Apple Computer. This new query is related to a different interest or topic that Palo Alto restaurants, and is therefore not grouped into the same session as the restaurant-related queries. Therefore the queries from a single user may be associated with multiple sessions. Two sessions associated with the same user will share the same cookie, but will have different session identifiers.”

Suffice to say the logging behind Google’s Search engine uses a specific series of methodologies to determine what a distinct search and distinct click are.

This may or may not align with what you believe or how your analytics platform is configured to believe a session is.

How Analytics Determines a Session

Analytics packages, on the other hand, also follow a series of methods for measurement of a user and their activity.

Depending on the analytics package, a “session” or a visit can be user-defined.

According to the Google Analytics documentation, “by default, a session lasts until there’s 30 minutes of inactivity, but you can adjust this limit so a session lasts from a few seconds to several hours.”

So, while we don’t know the exact timing of what Google Search considers a session, the numbers considered in the excerpts above are certainly less than 30 minutes.

In a patent related to Google Analytics, System and method for aggregating analytics data, the authors talk about how a user is tracked through a session ID and how that mechanism may become to be invalidated:

“A session ID is typically granted to a visitor on his first visit to a site. It is different from a user ID in that sessions are typically short-lived (they expire after a preset time of inactivity which may be minutes or hours) and may become invalid after a certain goal has been met (for example, once the buyer has finalized his order, he can not use the same session ID to add more items).”

As a result, a user can potentially be measured multiple times for the same visit.

Analytics packages are complex environments that allow for varying levels of specificity in their configuration.

There are numerous reasons why you won’t see consistency between two analytics packages let alone two tools that measure different things.

Why the Two Don’t Match Up

Simply put, a Google Search Console click is not a Google Analytics session and a Google Analytics session is not a Google Search Console click.

In the scenario above, wherein a user has clicked twice, that could be considered two clicks and one session.

Alternatively, if a user were to perform the two different searches and make two different clicks, their activity may be considered one impression and one click, but they could also invalidate their session ID or otherwise timeout at some point and be considered two distinct visits in analytics.

Or, consider this:

A user clicks on your result, but your analytics didn’t fire for any number of reasons. That speaks to any of the number of reasons why analytics isn’t always the most reliable source of truth.

Finally, GSC uses canonical URLs whereas analytics can use any URL for reporting a session. Google talks a bit about this in its documentation.

However, their discussion has more to do with explaining the differences within the context of the GSC to GA integration rather than explaining the differences in measurement methodologies

Why Is This a Problem?

The core problem is that many marketers don’t believe in GSC’s data because they consider analytics their primary source of truth.

Ignoring that all analytics is inherently flawed, I posit that parity between sources is unrealistic and we are looking at two sides of the same truth, just measured differently.

Performance data from Google Search Console is a measure of what’s happening on Google itself, not necessarily what is happening on your site.

Oh, and while we’re at it, don’t forget GSC’s position data is measuring something different than your rankings data.

How To Get More Precise Data

The precision of the data reported in Google Search Console actually increases as you introduce more specificity into how you review a website.

In other words, if you create profiles that reflect deeper levels of the directory structure, the tool yields more data.

It can be quite tedious to add 10s or hundreds of subdirectories to your Google Search Console, but the increase in data precision can prove to be quite helpful for use cases such as A/B testing and understanding breakout keyword opportunities.

When adding a wealth of profiles, the key limitation to keep in mind is that the GSC user interface limits you to 1,000 queries per search filter.

So, you should consider using the API to pull your data since it returns 5,000 per search filter.

Also, to extract as much data as possible, you should consider looping through a series of tries as search filters (S/O to William Sears).

This ensures that you’re using as many subsets of words as possible as filters to pull out as many results as possible.

Doing this by subdirectory and following your site’s taxonomy will allow you to get the most precise data possible.

Nothing Was the Same

Ever since the debut of “(not provided)” at the end of 2011, we knew our organic search data would erode.

Realistically, we will never live in a world where we can tie a visit directly to a session anymore.

The data that Google Search Console provides is the best that we will have moving forward.

While the data will not match up with your source of truth, that doesn’t mean it’s inaccurate.

The same way you shouldn’t expect Facebook Ads data to match up with Google Analytics or log files in Kibana to report the same as Adobe Analytics, you shouldn’t expect Google Search Console to match up with your analytics data.

Now, go out and be great.